So many are being offered induction of labour, often without a good medical reason. This blog article will help you to make sense- and make informed choices- in this complex and controversial area. So … [Read more...] about Labour Induction: Making Choices

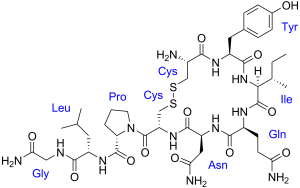

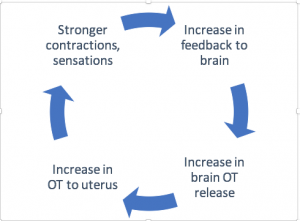

Hormonal Physiology, Oxytocin and More

Since the publication of her 2015 report Hormonal Physiology of Childbearing (more info and links here) Dr Buckley has continued to research and write about the hormones of physiological labour and … [Read more...] about Hormonal Physiology, Oxytocin and More

Synthetic Oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon): Unpacking the myths and side-effects

Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon) is widely used in maternity care around the world. It is commonly administered to induce or to speed up (augment) labour, and to prevent or treat bleeding … [Read more...] about Synthetic Oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon): Unpacking the myths and side-effects

How to Have the Best Cesarean

It's true that our female bodies are superbly designed, and that gentle, natural birth is the best possible start. But birth is ultimately mysterious and unpredictable, and can sometimes take its own … [Read more...] about How to Have the Best Cesarean

Does Synthetic Oxytocin (Pitocin) Cause Autism?

Does exposure in labour to synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon) cause autism? Or could exposure at least increase the risks of an autism spectrum condition, including milder forms of autism, for … [Read more...] about Does Synthetic Oxytocin (Pitocin) Cause Autism?

Should Every Mother be Induced at 39 Weeks? The ARRIVE Trial

If you are pregnant right now, you can’t have missed it. For maternity care providers, it’s been the topic of the year. Should healthy, low-risk women should be routinely induced at 39 weeks? On … [Read more...] about Should Every Mother be Induced at 39 Weeks? The ARRIVE Trial

The Best Possible Start: Resources for Expectant Parents

We have had the pleasure of welcoming 3 new nephews into our extended family in recent months. Congratulations to Alex and Dan, William and Temah, and Kate and Chris (pictured with Max) on your … [Read more...] about The Best Possible Start: Resources for Expectant Parents

The New Prenatal Testing

I was 35 when pregnant with my third baby, and 40 with my fourth. This put my babies in the ‘high risk’ category for chromosomal problems including Down Syndrome. Should I undergo testing to find out … [Read more...] about The New Prenatal Testing

Gentle Natural Birth for Modern Mamas

Gentle, natural birth is our genetic blueprint for labour and birth, switching on hormonal systems that optimise ease, pleasure and safety for mothers, babies, fathers and families. A gentle, … [Read more...] about Gentle Natural Birth for Modern Mamas

Covid-19 virus: Q&A for labour and birth

(Published April 30, 2020) We are living in uncertain times with the pandemic of Covid-19 illness, and this is especially intense for expectant families. This blog is intended to provide information … [Read more...] about Covid-19 virus: Q&A for labour and birth

In Praise of Midwives

Some people change the course of your life. My midwife Christine Shanahan, who passed away last month, changed my life, and the lives of literally thousands of mothers, babies, fathers and … [Read more...] about In Praise of Midwives

Epidurals in Labour (Part 2)

What do you know about epidurals and their risk and benefits? In this blog (Part 2), Dr Buckley explores the impacts of epidural on the hormones of labour and birth , and what this might mean for … [Read more...] about Epidurals in Labour (Part 2)

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!