Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon) is widely used in maternity care around the world. It is commonly administered to induce or to speed up (augment) labour, and to prevent or treat bleeding after birth (postpartum haemorrhage).

Like all maternity-care interventions, synthetic oxytocin may be beneficial, even life-saving, for mothers and babies in some situations. However, because of its widespread use, including in many healthy mothers and babies, it is important to understand the possible risks and side-effects.

This blog explores some important questions, including:

- Is synthetic oxytocin harmless because it mimics the natural oxytocin that women release during labour?

- Do high doses of synthetic oxytocin impact the mother’s own natural oxytocin release in labour?

In upcoming blog posts: (from mid-2023, make sure to sign up to my newsletter)

- Does synthetic oxytocin cross into the brain during labour?

- Could synthetic oxytocin affect breastfeeding or bonding?

- Does synthetic oxytocin cross to the baby?

- Could synthetic oxytocin impact the baby’s developing oxytocin system, as found in animal studies?

- Could synthetic oxytocin even cause autism? (Also see this blog)

This information in this blog comes from a recent publication on Maternal oxytocin levels during physiological childbirth, which Dr Buckley is a co-author (more details below) and a new review from Dr Buckley and colleagues of oxytocin levels in women and newborns following maternal synthetic oxytocin administration.

Is synthetic oxytocin harmless, because it mimics the natural oxytocin that women release during labour?

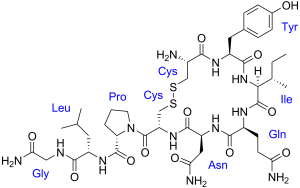

It is true that the chemical structure of synthetic oxytocin is identical to the chemical structure of the natural (endogenous) oxytocin that our bodies produce during labour, as shown in this picture.

It is true that the chemical structure of synthetic oxytocin is identical to the chemical structure of the natural (endogenous) oxytocin that our bodies produce during labour, as shown in this picture.

However, our own natural (endogenous) oxytocin is made in the brain and is released during labour into both the body, where pulses of oxytocin reach the uterus and promote the rhythmic contractions of labour, and also locally into the brain, where it has calming and pain-relieving effects.

As labour progresses, high oxytocin levels released within the brain help to counter the stress and pain of the strengthening contractions, which are caused by oxytocin stimulating the labouring female’s uterus. At the same time, oxytocin is activating her brain’s pleasure and reward centres in preparation for bonding with her newborn baby. (This process assists all mammals during labour, birth and postpartum )

In contrast, synthetic oxytocin is administered by intravenous (IV) infusion and in constant, high doses rather than in lower-levels and pulses. This can lead to maternal plasma oxytocin levels that are more than double those in a natural (physiological) labour, as measured in the blood. (See Oxytocin levels during physiological childbirth)

For these reasons, IV synthetic oxytocin causes contractions that are stronger and closer together than natural contractions, especially in early labour.

In addition, because synthetic oxytocin is administered into the body and not into the brain, it does not have the brain-based benefits of countering labour stress and pain, as natural oxytocin does. (See Oxytocin levels during physiological childbirth.) Therefore, the stress system may be more activated with high doses of synthetic oxytocin in labour, compared to physiological labour.

Those who are administered synthetic oxytocin also commonly receive epidurals to counter the increased pain, and epidurals reduce the natural release of oxytocin, as explained below and in this blog, which increases the need for synthetic oxytocin to fill the ‘hormonal gap.’

With this combination of epidural with synthetic oxytocin in labour, the natural stress-reducing benefits of endogenous oxytocin can be reduced or absent. (More about this below.) This combination might also explain some of the longer-term effects that have been reported for synthetic oxytocin, to be discussed in upcoming blog posts.

For the baby, the stronger and more frequent contractions will inevitably reduce blood and oxygen supply more than during physiological labour, increasing the risks of hypoxia (low oxygen), which is especially risky for the baby’s brain at this time. For this reason, administration of synthetic oxytocin in labour always requires monitoring of the baby’s heart rate to check for indications of hypoxia.

Some studies suggest extra risks of hypoxia and its possible long-term consequences for babies exposed to synthetic oxytocin in labour, although this area is not well studied. (See studies below.)

Synthetic oxytocin may also reduce activity in the uterine oxytocin receptors, although the mechanisms is not certain. This can decrease the effectiveness of oxytocin (natural or synthetic) to cause strong contractions, including after the birth. This explains why receiving synthetic oxytocin in labour increases the chance of postpartum haemorrhage and requires extra medications (including more synthetic oxytocin) to counter this risk. (More discussion of the possible mechanisms in upcoming posts.)

(For more great articles like this, make sure to sign up to my newsletter)

Do high doses of synthetic oxytocin impact the natural oxytocin release in labour?

It is sometimes presumed that administering high doses of synthetic oxytocin in labour will reduce maternal natural (endogenous) oxytocin production. This is not likely, according to our current understandings, although this is very hard to measure as natural and synthetic oxytocin can’t be differentiated in the blood.

It is important to understand that oxytocin release from the brain in labour is not controlled by the usual ‘negative feedback’ systems, whereby high levels of a hormone or biological marker lead to feedback that reduces levels. For example, our heart rate and blood pressure are controlled such that a sudden increases are detected by our body systems and lead to changes that bring them back down to what is normal for each of us. This negative feedback is operative in most biological systems, and contributes to homeostasis- the maintaining of physiological stability in the face of external (or internal) changes.

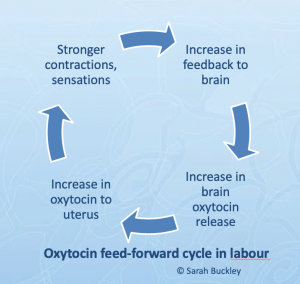

However, labour is not a homeostatic process! In labour, contractions need to strengthen rather than remain stable, and eventually be strong enough to push the baby from the mother’s uterus. This strengthening requires positive, rather than negative, feedback systems, also called ‘feed-forward cycles.’

This diagram shows one feed-forward cycle in labour, where strong uterine contractions cause pressure on the cervix area and generate sensory feedback to the brain that increases brain oxytocin release, including release to the uterus. This causes even stronger contractions and sensations, more sensory feedback and more oxytocin release.

This diagram shows one feed-forward cycle in labour, where strong uterine contractions cause pressure on the cervix area and generate sensory feedback to the brain that increases brain oxytocin release, including release to the uterus. This causes even stronger contractions and sensations, more sensory feedback and more oxytocin release.

This feed-forward cycle, also known as the Ferguson reflex, provides the high levels of oxytocin (average 3-4-fold increased at birth) that are needed for the birthing mother to have an effective pushing stage.(See Oxytocin levels during physiological childbirth)

The administration of synthetic oxytocin (without epidurals) will not reduce this cycle, or the stimulation of natural oxytocin release. In fact, in some circumstances, synthetic oxytocin may even accelerate this feed-forward cycle (and increase brain oxytocin) by causing stronger contractions with greater sensations. (More details in upcoming blog posts.)

However, when epidurals are co-administered, the sensations from contractions, which fuel this feed-forward cycle, are abolished, which slows or even stops the cycle, and consequently slows or stops oxytocin release, as described in this blog.

The combination of epidurals with high doses of synthetic oxytocin can therefore increase physiological stress in labour but reduce oxytocin release, including within the brain, which would usually counteract this stress in labour.

In summary

Synthetic oxytocin is chemically identical to the natural oxytocin released in labour and birth. However it has different effects because it is administered IV rather than into the brain.

In contrast, natural oxytocin is released from and into the brain in labour, and gives calming, pain relieving effects that counteract labour stress and pain. Within the brain, natural oxytocin also activates reward and pleasure centres in preparation for bonding with the newborn baby.

While synthetic oxytocin may not directly reduce the natural release of oxytocin, the common co-intervention of epidural analgesia does significantly reduce oxytocin release. Epidurals can slow labour and reduce oxytocin’s anti-stress, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant benefits. This combination might explain some of the longer-term effects that have been found for synthetic oxytocin, which will be discussed further in later blogs.

In addition, prolonged, high doses of synthetic oxytocin increase the risk of bleeding after birth (postpartum haemorrhage). This likely reflects disruption to uterine oxytocin receptors, making the uterus less responsive to oxytocin and increasing the risk of bleeding, although the mechanism is debated.

Upcoming blog posts:

- Does synthetic oxytocin cross into the brain during labour?

- Could synthetic oxytocin interfere with the new mother’s ability to bond with her baby?

- Could synthetic oxytocin impact breastfeeding success?

- Does synthetic oxytocin cross to the baby?

- Could synthetic oxytocin impact the baby’s developing oxytocin system, as found in animal studies?

- Could synthetic oxytocin even cause autism? (Also see this blog)

(For more great articles like this, make sure to sign up to my newsletter)

References and resources

Much of this information comes from a new publication on Maternal oxytocin levels during physiological childbirth: A systematic review with implications for uterine contractions and central actions of oxytocin This was written with the good work and dedication of colleagues Kerstin Uvnas Moberg, Anette Ekstrom-Bergstrom and other European co-authors. This work was partly funded by EU COST IS1405 BIRTH: Building intrapartum research through health.

Hormonal Physiology of Childbearing report Sarah’s 2015 report with lots of information about oxytocin (Free download)

Sarah’s 2-part blog on epidural effects, including oxytocin

Impacts of synthetic oxytocin in labour:

- Oscarsson 06: Higher newborn risks in a population study

- Clark 2008: Preventable adverse newborn outcomes

- Buchanan 12: Worse outcomes for mothers and babies

- Drummond 18: Legal views on synthetic oxytocin in labour

Note that these studies are observational and do not imply causation. However, there is very little high-quality research available in this area.

Bugg 13 : Augmentation with synthetic oxytocin has minimal benefits (Cochrane review)

Rahm 2012 : Epidurals reduce oxytocin

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!