I was 35 when pregnant with my third baby, and 40 with my fourth. This put my babies in the ‘high risk’ category for chromosomal problems including Down Syndrome. Should I undergo testing to find out if my baby was affected, involving procedures that would increase the chance of losing my baby? Or should my partner and I accept the small chance that our baby could be affected, with the knowledge that this would have a huge impact on our family and lives?

In the years since I faced those decisions for myself– you’ll have to read to the end to see what we chose–prenatal testing has become more simple and also more complex. It is simpler because the newest tests require just a blood test, but much more complex because of the vast amount of information that can potentially be gained, even before our babies are born.

However, fundamentally, our choices are the same: how much information do we want to know about our unborn baby, and would we consider a termination of pregnancy if the news was bad?

However, fundamentally, our choices are the same: how much information do we want to know about our unborn baby, and would we consider a termination of pregnancy if the news was bad?

Prenatal testing is generally focussed on our unborn babies’ chromosomes—the tiny strands of DNA that are present in every cell, as our blueprint for development. The chance of chromosomal abnormalities increases with the mother’s age, but younger mothers can also have babies with chromosomal conditions. Down syndrome is the most common, at around 1 in 1000 live births, although many babies with Down syndrome miscarry before birth.

Until recently, we have used complex and largely indirect “screening” tests for chromosomal conditions. Screening tests tell us our baby’s chance of abnormalities, rather than giving a definite result.

Screening tests include maternal blood levels at early to mid-pregnancy (‘triple’ and ‘quadruple’ screening) and specialised ultrasound scans that assess markers such as the thickness of the baby’s neck fold (‘nuchal translucency screening’ or NTS) or the nasal bone. Blood tests and scans may be used in combination to get the most accurate screening results.

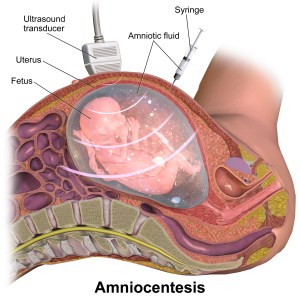

Positive screening tests are followed up with definitive but invasive testing, which requires a sample of the baby’s cells. As you might imagine, using a needle to sample the amniotic fluid (“amniocentesis”) or taking a piece of the baby’s placenta (chorionic villus sampling, CVS), even in the most skilled hands and with ultrasound guidance, can potentially cause harm, especially miscarriage. This extra risk of miscarriage has made doctors cautious about the use of invasive tests, generally limiting them to women at ‘high risk’, either from screening results or because of older age.

Positive screening tests are followed up with definitive but invasive testing, which requires a sample of the baby’s cells. As you might imagine, using a needle to sample the amniotic fluid (“amniocentesis”) or taking a piece of the baby’s placenta (chorionic villus sampling, CVS), even in the most skilled hands and with ultrasound guidance, can potentially cause harm, especially miscarriage. This extra risk of miscarriage has made doctors cautious about the use of invasive tests, generally limiting them to women at ‘high risk’, either from screening results or because of older age.

However, the new ‘non-invasive prenatal testing’ (NIPT) is rapidly overshadowing these traditional screening methods. If you are pregnant in a high-resource country, you are likely to be offered this test, which currently costs several hundred dollars.

NIPT is also called cell-free fetal DNA (cfDNA). It is a simple blood test at around 10-13 weeks that analyses the tiny amounts of the baby’s DNA that find their way into the mother’s bloodstream. NIP is around 99% accurate for Down syndrome and can also detect many other genetic conditions with a slightly lower degree of accuracy.

In some places, NIPT is used to give additional information when a routine screen shows a ’high risk’ result. In other places, NIPT is available as a first-line testing, with invasive testing used when abnormalities are found. Because of cost, NIPT may not be available as part of routine care, but the cost is likely to reduce with wider use.

Currently, NIPT is limited to detecting conditions that traditional testing picks up: Down syndrome, along with Edwards and Patau syndromes. These are all ‘trisomies’, where three copies of a chromosome are created, instead of two. Trisomies often lead to miscarriage, and babies born with Edwards and Patau syndromes do not usually survive the first year of life. However, children with Down syndrome and their families can lead happy and fulfilling lives.

Currently, NIPT is limited to detecting conditions that traditional testing picks up: Down syndrome, along with Edwards and Patau syndromes. These are all ‘trisomies’, where three copies of a chromosome are created, instead of two. Trisomies often lead to miscarriage, and babies born with Edwards and Patau syndromes do not usually survive the first year of life. However, children with Down syndrome and their families can lead happy and fulfilling lives.

NIPT also analyses your baby’s ‘sex chromosomes’–the X and Y that make us females (XX) or male (XY). As well as gender, NIPT can also detect sex chromosome variations such as Turners (XO) and Klinefelters (XXY) syndromes, which are not lethal but generally have some reproductive and other effects.

There are more babies in the womb who have sex chromosome abnormalities (1/4-500) than Down syndrome (1/700-1000). Many of these sex chromosome abnormalities have unknown effects, and it is likely that many of us are walking around with what would be diagnosed as abnormalities in our sex chromosomes that actually have no impact on our development, lives or fertility. However, the lack of certainty–what exactly this test result means for this baby–is understandably difficult for parents.

The conditions that are currently tested with NIPT are just a fraction of what can possibly be detected. New techniques mean that we could soon know our unborn baby’s chance of breast cancer in later life, for example, through BRCA genes. This may be very helpful for families with strong genetic conditions, but the ethical and practical implications are enormous for all of us.

These tests were not available when we made our choices and, to be honest, would not have swayed me. In consultation with my partner, I chose to have no testing with either pregnancy. I realised that didn’t want to have more information than I needed, and especially to chance the uncertain findings that would have made my pregnancy a time of anxiety and fear, rather than joyful expectancy, and may have distanced me from my baby, even after birth. I also decided that I would not terminate my wanted pregnancies, and if my baby had a condition that was not compatible with life, I would let Nature takes its course.

These tests were not available when we made our choices and, to be honest, would not have swayed me. In consultation with my partner, I chose to have no testing with either pregnancy. I realised that didn’t want to have more information than I needed, and especially to chance the uncertain findings that would have made my pregnancy a time of anxiety and fear, rather than joyful expectancy, and may have distanced me from my baby, even after birth. I also decided that I would not terminate my wanted pregnancies, and if my baby had a condition that was not compatible with life, I would let Nature takes its course.

These are obviously very personal decisions, and there are no one-size-fits-all answers. High-quality, non-judgemental information and discussion is needed, even before we make the first choice. We need to consider our answers to these basic questions- how much information do we want to know about our unborn baby, and would we consider a termination of pregnancy if the news was bad?

You can read my in-depth chapter on prenatal testing (not including NIPT) in my 2005 Gentle Birth, Gentle Mothering ebook.

Resources

For parents

General information on genetics

Fact sheet on prenatal testing for Down syndrome

Welcoming babies with Down syndrome

Women’s experiences

What is a healthy baby anyway?

Books

Information aimed at professionals

Reducing the anxiety of Prenatal Testing

Reading

Prenatal Testing: Technological triumph or Pandora’s box? In Sarah’s 2005 Gentle Birth, Gentle Mothering ebook.

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!