So many are being offered induction of labour, often without a good medical reason. This blog article will help you to make sense- and make informed choices- in this complex and controversial area.

So many inductions

In Australia (2020) labour was induced in more than 1 in 3 pregnancies (35.5%), including almost half (45.8%) of first-time pregnancies. The US Vital Statistics (2021) reports 32.1% induction (2021), although women themselves report higher induction rates- as reported in the Listening to Mothers surveys. Rates are high in many other countries, suggesting that maternity-care interventions are being applied ‘too much, too soon’.

Why am I being offered an induction?

If you have been offered an induction of labour without a medical reason, especially in your first pregnancy, it is likely because of the 2019 ARRIVE trial.

This study found that routinely inducing labour at 39 weeks in a healthy, low-risk first-time pregnancy  reduced the caesarean rate from 22.2% to 18.6% (16% reduction) with no other signficant benefits. (See my blog critique here and note the even greater reduction in caesareans- 25%- from doula care.)

reduced the caesarean rate from 22.2% to 18.6% (16% reduction) with no other signficant benefits. (See my blog critique here and note the even greater reduction in caesareans- 25%- from doula care.)

The ARRIVE trial has influenced practice world-wide because it provides supposedly the best evidence- a randomised controlled trial (RCT)- in this controversial area. However, RCTs have strict criteria for inclusion and treatment, and results may be different in real-life situations, outside experimental conditions. This problem is called ‘external validity.’ (See this discussion of the external validity of the ARRIVE trial.)

In fact, many studies have found that, in everyday practice settings, induction has minimal or even negative effects on caesarean rates, and may increase other risks. See this large study, this study and this high-quality review. This is a controversial area and results depend on the groups compared, the timing of induction and the rates of induction in the group who were not initially induced (‘expectantly managed.’)

Has this improved outcomes?

Have the increasing numbers of inductions improved outcomes, as the ARRIVE trial suggested?

This study used US data to compare the outcomes for healthy, low-risk, first-time pregnancies before (2015-7) and after (2019) publication of the ARRIVE trial. Induction rates increased from 30% to 36% in this population, but their CS rate decreased only 0.6%. In addition, there were higher risks of some concerning outcomes in the induced groups, including more serious postpartum haemorrhage, lower newborn APGAR scores and more newborn breathing difficulties.

Could induction disrupt hormonal processes?

There are very complex and precise processes that lead to the physiological (spontaneous) onset of labour. These processes ensure that mother and baby are both perfectly prepared for an effective labour, birth and postpartum/newborn transitions, including breastfeeding and bonding. By definition, this readiness is not complete when birth is scheduled by induction or prelabour CS.

For a detailed review of the processes involved with the physiological onset of labour, see Chapter 2 , ‘Physiologic Onset of Labor and Scheduled Birth’ in my 2015 Hormonal Physiology report, linked from my website here and a more recent article here.

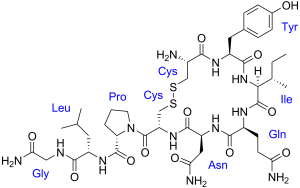

In addition, the method of induction may disrupt the natural hormonal flow of labour. As part of my PhD, I’ve been publishing studies with EU colleagues looking at oxytocin levels in women and babies in labour and the effects of interventions. Our upcoming reviews include studies of prostaglandins and rupture of membranes.

(To keep updated with my research, make sure to sign up to my newsletter)

Oxytocin and Induction: My PhD research

In our most recent publication we summarised all the studies that measured plasma (blood) oxytocin levels in women receiving synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon).

In our most recent publication we summarised all the studies that measured plasma (blood) oxytocin levels in women receiving synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon).

We found that, even with the highest doses in labour, maternal oxytocin levels were maximum 3-4 times higher than levels in physiological labour. This is not high enough to cross the placenta or into the maternal brain and cause direct harm. (However, indirect effects are possible, including effects from the additional stress and pain of induction- see our discussion here)

We also found that newborn babies have naturally high oxytocin levels in labour, likely due to the stress and massage-like effects of uterine contractions. These high oxytocin levels help the baby cope with labour and adapt to life outside the womb. Being exposed to synthetic oxytocin did not further increase newborn oxytocin levels, indicating that synthetic oxytocin does not cross to the baby in labour.

My next blog will discuss these findings further- stay tuned! We are also researching the effects of epidural, opioids and prostaglandins in upcoming publications.

Another important question is: could labour induction-whether with synthetic oxytocin or other methods- affect longer-term outcomes such as breastfeeding, bonding and postpartum depression? These outcomes have not been well studied in the highest-quality randomised trials and are part of my PhD studies.

(To keep updated with my research, make sure to sign up to my newsletter)

Brain development in the womb

There are also a growing number of studies suggesting worse development and educational outcomes in children born at shorter gestation, even at 39 vs 40 or 41 weeks. This is not surprising when we consider that the unborn baby’s brain is growing at a very fast rate at the end of pregnancy, making those last weeks of brain development very precious. (See Every Week Counts) Shortening gestation with induction could limit full brain development. See also my discussion here.

However, some studies looking at induction and longer-term offspring outcomes have not found negative effects. Induction rates in the expectant groups are an important consideration in these studies. It is also important to note that these population-wide studies do not mean that being induced will have effects on individual children.

Are there benefits from labour induction?

There is no doubt that induction of labour reduces the chances of stillbirth. Babies that have been induced and born are obviously not at risk of stillbirth. This has been a major motivation for induction past 40-41 weeks, although the actual risks (and therefore benefits of induction) are small.

Some babies that are overdue do not cope as well with labour. This has been used to disallow access to midwifery care in birth centres or homebirth past 41 or 42 weeks. However, again the risks are small. If you are labouring after 41-42 weeks, your care provider or midwife may want to monitor you more closely.

Based on these considerations, induction at 41-42 weeks may prevent 2 perinatal deaths (around the time of birth) per 1000 babies. Looked at another way, 544 inductions would be needed to prevent the death of one baby. This information may be helpful if you are overdue and offered an induction of labour.

The best decision

Ultimately the best decision is one you make with your heart and womb, connected to your baby, as well as with the information from here and the resources below.

(To keep updated with my research, make sure to sign up to my newsletter)

More induction resources:

Postdates induction of labour- balancing risks Rachel Reed- Midwife thinking

Ten things I wish women knew about induction- Sarah Wickham and her books

Induction of labour (Podcast)- Melanie the Midwife with Hannah Dahlen in The Great Birth Rebellion

Inducing for due dates Evidence based birth

Induction of labour articles Henci Goer

Myth of the aging placenta –Sophie Messager

Preventative induction of labor- does Mother Nature know best? (ARRIVE trial) Lamaze international

Your body, your baby, your choice: Chapter 4 in Gentle Birth, Gentle Mothering by Dr Sarah Buckley

Acknowledgements:

Some of this information comes from a new publication as part of my PhD research: Maternal and newborn plasma oxytocin levels in response to maternal synthetic oxytocin administration during labour, birth and postpartum – a systematic review with implications for the function of the oxytocinergic system This was written with the good work and dedication of my colleagues Kerstin Uvnäs-Moberg, Zada Pajalic, Karolina Luegmair, Anette Ekström-Bergström, Anna Dencker, Claudia Massarotti, Alicja Kotlowska, Leonie Callaway, Sandra Morano, Ibone Olza & Claudia Meier Magistretti. This work was initiated within EU COST IS1405 BIRTH: Building intrapartum research through health.

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!