So many are being offered induction of labour, often without a good medical reason. This blog article will help you to make sense- and make informed choices- in this complex and controversial area. So … [Read more...] about Labour Induction: Making Choices

Pitocin myths and side-effects

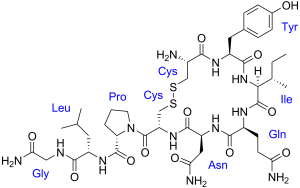

Synthetic Oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon): Unpacking the myths and side-effects

Synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon) is widely used in maternity care around the world. It is commonly administered to induce or to speed up (augment) labour, and to prevent or treat bleeding … [Read more...] about Synthetic Oxytocin (Pitocin, Syntocinon): Unpacking the myths and side-effects

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!

Discover the science and pleasure of Ecstatic Birth!